Harnessing Kairos: Balancing Structured Time and Learning Velocity in K-12 Classrooms

Time in education is about more than minutes on the clock or adhering to rigid schedules. It’s about how students experience time cognitively and emotionally in the learning process. A deeper dive into these ideas reveals actionable ways to create meaningful learning experiences for students.

Educational philosopher Shari Tishman describes this beautifully in her work, Slow Observation: The Art and Practice of Learning. She reminds us that observation and understanding happen through repeated encounters with ideas and experiences—’re-searching’ in the truest sense. Similarly, educators must question how ‘time’ and ‘space’ function in classrooms and how they enhance or limit learning.

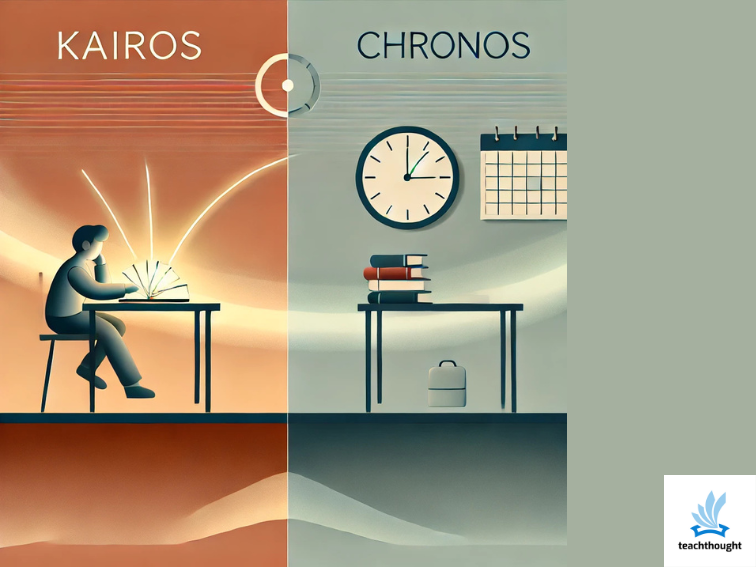

This brings us to the ancient Greek concepts of time: Chronos and Kairos.

Chronos refers to chronological, measurable time—class periods, units, pacing guides.

Kairos refers to opportune moments, when time and readiness align to spark understanding and insight. In teaching, Kairos often happens when students connect ideas in their own unique ways and at their own pace.

Kairos refers to the opportune moments for learning, emphasizing a student’s readiness and cognitive state to engage with knowledge in a meaningful way. Chronos, on the other hand, represents chronological, structured time in education, focusing on scheduled periods, lesson plans, and the pacing of material delivery.

Shifting from Chronos to Kairos in the Classroom

Too often, modern education focuses exclusively on Chronos—structured schedules, standardized tests, fixed lesson plans—while neglecting Kairos, the individualized cognitive ‘space’ that empowers students to explore, question, and develop critical thinking skills. This tendency puts students into one-size-fits-all molds and overlooks individual learning ‘velocities.’

See also Critical Thinking Is A Mindset

In practical terms, learning velocity is the pace at which a student processes, absorbs, and applies knowledge. Some students process quickly, demonstrating strong memorization and performing well on timed assessments. Others take more time to explore ideas, ask questions, or internalize new information, leading to deeper critical thinking and stronger problem-solving skills. Both approaches are valuable, and good teaching makes room for both.

One Example Of Kairos And Chronos

- A fast processor in math might quickly memorize formulas but struggle to apply them to real-world problems.

- A slower processor might take longer to understand the formulas but develop deeper applications and connections over time.

Neither is inherently better or worse; they are simply different manifestations of learning. The teacher’s role is to recognize and honor these differences, creating a balance between the structure of Chronos and the flexibility of Kairos.

Kairos refers to the opportune moments for learning, emphasizing a student’s readiness and cognitive state to engage with knowledge in a meaningful way. Chronos, on the other hand, represents chronological, structured time in education, focusing on scheduled periods, lesson plans, and the pacing of material delivery.

The difference lies in that Kairos centers on the qualitative aspects of learning—how and when a student is most receptive—while Chronos is concerned with the quantitative measurement of time allocated for instruction. Effective teaching should harmonize both concepts, using chronological planning to support the cultivation of Kairos moments that foster deeper understanding and critical thinking.

6 Simple Strategies For Reclaiming Kairos In The Classroom

Build in Open-Ended Exploration

Allow students time to engage with material deeply, especially after introducing a new concept. For example, after a direct instruction session on the Civil Rights Movement, provide space for students to ask questions or research specific figures or events that interest them.

Incorporate Reflection Time

Reflection is helpful for slower cognitive processing and creates new connections for students. Use journaling, silent thinking time, or reflective discussions after a lesson to encourage students to process at their own pace.

Offer Flexible Pacing Options

If homework, projects, or assessments have hard deadlines, allow flexible pathways for completion. For instance, provide tiered assignments where students can choose a base-level task or optional extensions to push deeper thinking.

Use Multiple Learning Modalities

Balance structured activities (e.g., worksheets and quizzes) with more exploratory opportunities such as group work, projects, or debates to engage both faster and slower learners. A science inquiry project, for example, could include space for both quick experiments and in-depth research.

Redefine Success

Move beyond metrics that attribute higher achievement only to speed or memorization. For instance, assess critical thinking through open-ended questions, projects, or portfolios that include evidence of deliberation and creativity, not just speed.

Understanding the Impact of Mind-Space

Teaching for Kairos not only supports individual learning velocities but also fosters independence and critical thinking. Importantly, it shifts the focus from “what to learn” to ‘how to learn.’ When students have the freedom to explore their unique pace and processing styles, they gain an understanding of themselves as learners.

Consider a student who struggles with timed reading comprehension tests may excel in writing essays that allow time for thought and creativity. Without opportunities to explore this strength, that student might disengage from the learning process altogether. Creating ‘Kairotic space’ prevents this kind of disconnect, allowing students to define their own success.

Closing Thoughts

Reclaiming Kairos in classrooms requires intentionality. From rethinking lesson plans to building in opportunities for exploratory and reflective learning, every teacher has the ability to create mind-spaces that have the best chance of helping students learn.

In the end, honoring learning velocity means acknowledging that students don’t just need time in the classroom—they need space within the classroom to grow, question, and develop understanding at their own pace. When this happens, students achieve not just as learners but as critical thinkers prepared for a lifetime of exploration/